|

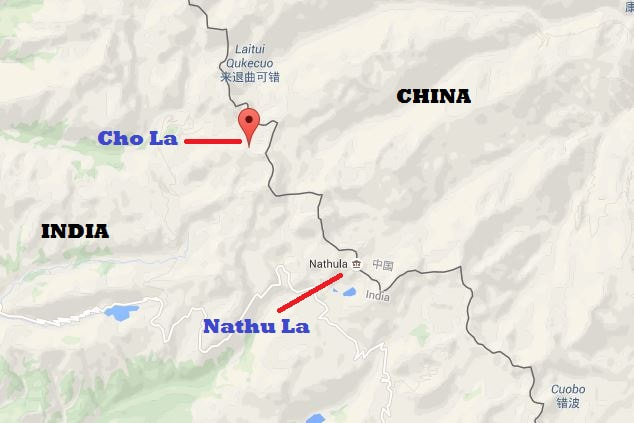

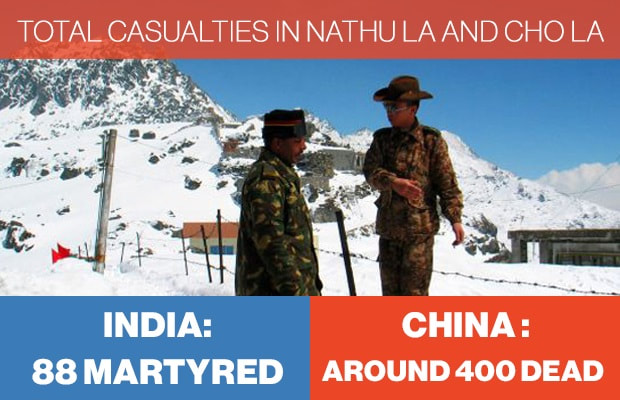

That India lost the 1962 war against China is known to all. Yes, it was a defeat but it was the defeat for the then political top brass who consistently ignored the warning given by Indian Army and Intelligence and not the military which fought like lions despite being outnumbered and outgunned. The loss to China was not forgotten. A more aggressive Indian military was born and just three years later, in 1965, India defeated Pakistan. Yet China believed that since they had defeated us in 1962, we would not be a match to their military might ever. But perhaps too drunk over their win in 1962, the Chinese had underestimated the Indian Army. Barely five years later had the neighboring nations militarily clashed again. This time the battleground was Nathu La. The Sikkim clashes came even as American troops were fighting in Vietnam, in the midst of Chairman Mao’s unfolding Cultural Revolution, and a few months after China had conducted its first hydrogen bomb test. A major contributor to this inter-country battle is speculated to be the apparent dispute between India and China regarding the disputed border land in Chumbi valley. In addition to the disputed border, India and China have always been at loggerheads with one another, and the reasons are endless. Chinese are mainly angry about the fact that India are not submitting to their pressures and their bullying. They would like India to fall in line with their strategy or their policy of dominating Asia and, ultimately, the world. The Nathu La and Cho La battles were India’s comeback into the world-avenue of military consciousness. Both the sides fought just as fiercely, but India stood unbeatable. China was embarrassed enough to disclose heavily tampered figures of their casualties, as well as monetary loss while India held on to candour. Why Nathu La Nathu La is a strategically important pass 14,200 feet above sea level. It was then all the more important because Sikkim was not part of India at the time. It was a protectorate state with the Indian Army deployed on its borders to safeguard it from external aggression. Unhappy with this fact, China asked India to vacate the mountain pass of Nathu La on the Sikkim-Tibet border during the Indo-Pak war of 1965. China wanted India to vacate Sikkim and take control. Imagine what would have happened if India had done that. The Chinese border would have been at West Bengal and, perhaps, the seven states of the northeast would not have been India’s part. When the Indian Army refused to accede to this ultimatum, China began resorting to tactics of intimidation and attempted incursions into Indian Territory. On June 13, 1967, China expelled two Indian diplomats from Peking (now Beijing) accusing them of espionage while keeping the rest of the staff captive inside the embassy compound. Starting from 13 August 1967, Chinese troops started digging trenches in Nathu La on the Sikkimese side. Indian troops observed that some of the trenches were "clearly" to the Sikkemese side of the border, and pointed it out to the local Chinese commander, who was asked to withdraw from there. Yet, in one instance, the Chinese filled the trenches again and left after adding 8 more loudspeakers to the existing 21. Indian troops decided to stretch a barbed wire along the ridges of Nathu La in order to indicate the boundary. So when the PLA hoisted 29 loudspeakers on the Sikkim-Tibet border and began warning the Indians of a fate similar to 1962, India decided to fence the border with barbed wire to make sure Chinese did not have an excuse for border violations. The work started on August 20. Clashes at Nathu La The stand-off began as engineers and jawans started erecting long iron pickets from Nathu La to Sebu La along the perceived border, which was agreed by both sides under the 1890 treaty between Great Britain and Qing Dynasty China. Chinese troops objected vociferously to the laying of the wire, leading to an argument between the PLA Political Commissar and the Commanding Officer of the Indian Army infantry battalion, Col. Rai Singh. On September 7, a scuffle ensued — the memories of 1962 were still fresh in the minds of both the armies. Three days later, China sent a terse warning through the Indian embassy, calling Indian leaders “reactionaries” who were “component part of the worldwide anti-Chinese chorus currently struck up by US imperialism and Soviet Revisionism in league with the reactionaries of various countries”. On the fateful morning of September 11, when an undaunted Indian Army started work, PLA troops came back to protest. Col. Rai Singh went out to talk to them. Suddenly, the Chinese opened a burst of fire from their medium machine guns (MMGs). Seeing their wounded Commanding Officer hit the ground, two brave officers (Captain Dagar of 2 Grenadiers and Major Harbhajan Singh of 18 Rajput) rallied the Indian troops and attacked the Chinese MMG post. Caught in the open (Nathu La Pass is devoid of any cover), the Indian soldiers suffered heavy casualties, including the two officers, who were both given gallantry awards for their bravery. By this time, the Indian army had started responding with heavy artillery fire, pummeling every PLA post in the vicinity. Bolstered by fierce close-quarter combat by the Mountaineers, Grenadiers and Rajputs, this counter-attack decimated the Chinese positions in the next three days. Taken aback by the strength and ferocity of the Indian response, the Chinese threatened to bring in warplanes. Having driven its message home militarily, India agreed to an uneasy ceasefire across the Sikkim-Tibet border. The Chinese, true to form, had pulled over dead bodies to their side of the perceived border at night and accused India of violating the border. Dead bodies were exchanged on 15 September at which time: Sam Manekshaw, [then Eastern Army Commander], Aurora [Lt Gen Jagjit Aurora, Corps Commander] and Sagat [Maj Gen Sagat Singh, GOC Mountain Division in Sikkim] were present on the Pass. Clashes at Cho La But a belligerent PLA was still looking for trouble. On the morning of October 1, 1967, a Chinese platoon got into a heated argument with a forward platoon commander (Naib Subedar Gyan Bahadur Limbu) over the ownership of a boulder demarcating the boundary at Cho La, another pass on the Sikkim-Tibet border a few kilometres north of Nathu La. In the ensuing scuffle, the Chinese bayoneted Limbu and took up aggressive positions, escalating the situation. But the Chinese forgot that they were facing the famously gritty Gorkhas (of the newly formed 7/11 Gorkha Regiment). Standing their ground, the Indian troops retaliated with a fierce counterattack against the enemy who was forming up for an assault. Section commander Lance Naik Krishna Bahadur led this charge and was hit by thrice by Chinese bullets. Despite being unable to use his weapon, the injured braveheart nevertheless urged his men on, gesticulating with his khukri till he was ultimately killed in a machine-gun volley. Rifleman Devi Prasad Limbu charged at the Chinese with his Khukri after all his ammunition had finished, taking five of them down before he too was martyred. His raw courage was later honoured with the Vir Chakra. Another Vir Chakra was awarded to Havildar Tinjong Lama, who used his 57mm recoilless gun with deadly accuracy to knock out a heavy machine gun being used by the Chinese to unleash withering fire. Colonel KB Joshi, the commanding officer, too personally led a company attack to recapture Point 15,450. The intense gunbattle at Cho La pass continued for the next 10 days, ending with the crushing defeat of the PLA soldiers. Such was the upper hand achieved by the Indian Armies fierce reaction to Chinese provocations that the PLA was forced to withdraw for three kilometres to a feature named Kam Barracks, where they remain deployed till date. Casualties According to Chinese reports, the number of soldiers killed were 32 on the Chinese side and 65 on the Indian side in Nathu La incident; and 36 Indian soldiers and an 'unknown' number of Chinese were killed in the Cho La incident. On the other hand, the Indian Defence Ministry reported: 88 killed and 163 wounded on the Indian side, while 340 killed and 450 wounded on the Chinese side, during the two incidents. Aftermath

The 1967 incident marked the last incident of casualties on both sides in the Sikkim sector. And the last death in any sector of the India-China border was in 1975 at Tulung La, and that was by accident, when two patrols were lost in the fog. So despite the close parallels, 50 years on history is unlikely to repeat itself with the border remaining largely tranquil in the decades since. |

AuthorPalash Choudhari Archives

June 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed